EDUCATION/TRAINING

Busting Top Trauma MythsBY KEVIN T. COLLOPY, BA, FP-C, CCEMT-P, NREMT-P, WEMT, SEAN M. KIVLEHAN, MD, MPH, NREMT-P,SCOTT R. SNYDER, BS, NREMT-P ON MAR 2, 2015

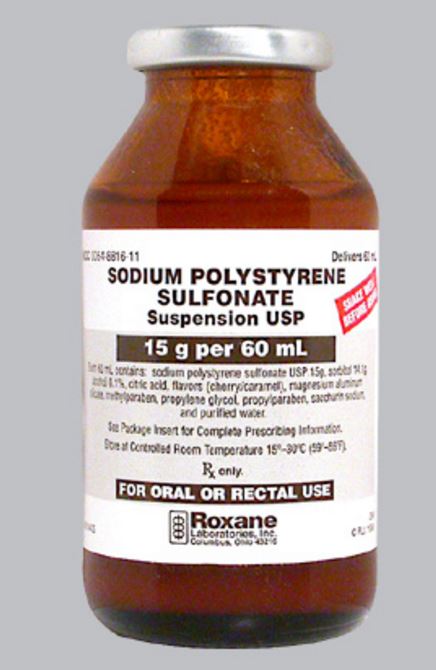

Hyperkalemia treatment is a core skill for emergency physicians and an area in which we excel. Give calcium to stabilize cardiac myocytes if there are ECG changes, insulin (plus dextrose), albuterol, and sodium bicarbonate to shift potassium into the cell, and then sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS; brand name Kayexalate) to eliminate the potassium from the body, right?

There are areas to debate within each of these steps, but I want to address the final one. SPS is a cation-exchange resin that was approved in 1958 as a treatment for hyperkalemia by helping to exchange sodium for potassium in the colon and excreting potassium from the body. The wide adoption of SPS for this indication comes from two articles published in the New England Journal of Medicinemore than 50 years ago.

Treatment of the Oliguric Patient with a New Sodium-Exchange Resin and Sorbitol; A Preliminary Report

Flinn RB, Merrill JP, Welzant WR New Engl J Med 1961;264:111Flinn and colleagues studied 10 patients with severe oliguria that were given a cation-exchange resin and sorbitol (n=7) or sorbitol alone (n=3) along with no-potassium diets. They found that potassium decreased by 0.5 mEq on the first day and a total of 1.0 mEq after two days. Sorbitol alone was just as effective. They noted that a dose of around 40 mEq/day should be the recommended dose, but this is based on no data or reference of any kind.

Management of Hyperkalemia with a Cation-Exchange ResinScherr L, Ogden DA, et al. New Engl J Med 1961;264:115

This slightly larger study looked at 32 patients with acute or chronic renal failure who were given oral or rectal SPS along with a low- or no-potassium diet. Scherr and colleagues found a mean decrease in potassium at 24 hours of 1.0 mEq.

The Flinn and Scherr studies conclude that the use of cation-exchange resin plus sorbitol is beneficial to treat hyperkalemia. The results of their studies, however, simply do not support this conclusion. The Flinn study looked primarily at outcomes 120 hours after administration. This is hardly the endpoint that we care about in the emergency department. (I would argue that even the inpatient clinicians wouldn't care about this endpoint.) The Scherr study had no control group, and the decrease was seen at 24 hours. Again, not what we would care about in the ED. Both studies lacked even a modicum of randomization, and all patients were given low- or no-potassium diets. These studies from the New England Journal of Medicine are the basis upon which kayexlate has been prescribed for five decades, and it's pretty clear that they prove nothing.

The scant literature on this topic was summed up in a Cochrane review in 2005 that stated that potassium-absorbing resins have never been found to be effective in the first hours of treatment. (Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; http://bit.ly/1HWfR4W.)

A review of the literature shows that there is virtually no benefit in the emergent setting for SPS. But is there a downside? Of course, though we are talking about a rare but highly lethal complication of the drug: colonic necrosis.

A number of case reports and case series detail patients with SPS-associated colonic necrosis. (Surgery 1987;101[3]:267; Am J Kidney Dis 1992;20[2]:159; J Trauma 2001;51[2]:395; Am J Emerg Med2009;27[6]:753.e1.) In fact, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration added a warning in 2011 cautioning against the use of the drug for this reason. (http://1.usa.gov/1DHhPLp.)

Given the absence of any significant benefit, particularly in the emergent setting, and the potential for serious harm, this recommendation from the nephrology literature seems very reasonable: “It would be wise to exhaust other alternatives for managing hyperkalemia before turning to these largely unproven and potentially harmful therapies.” (J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21[5]:733.)

Initially, it's worth briefly discussing the recent publications highlighting two new drugs targeted at eliminating potassium. Sodium zirconium cycloscilicate and patiromer are cation-exchange drugs, and studies on these drugs have been published in high-impact journals. (New Engl J Med 2015;372[3]:222; JAMA 2015;314[2]:151; New Engl J Med 2015;372[3]:211.) Both drugs have been hailed by researchers (all with significant conflicts of interest) as highly successful in managing hyperkalemia. Before we get too excited, though, both agents have only been studied in small groups of patients with mild to moderate asymptomatic hyperkalemia and not in ED patients. The primary outcomes in these studies were potassium reduction over weeks, which is an outcome that's not relevant in ED patients.

So what should we do with the hyperkalemic patient?

* If he has EKG changes, give Ca2+ salts and standard temporizing therapy and get the patient dialyzed if necessary.

* If you have to wait for dialysis, continue to redose your temporizing meds.

* Look for the underlying cause. Missed dialysis? ACEI? NSAIDs?

Save your patient, yourself, and your nurses from dealing with the unpleasant after-effects of SPS (i.e., diarrhea) by avoiding this ineffective and potentially dangerous medication.

Read more at:

http://journals.lww.com/em-news/Fulltext/2015/10000/Myths_in_Emergency_Medicine__Kayexalate_for.3.aspx

Busting Top Trauma MythsBY KEVIN T. COLLOPY, BA, FP-C, CCEMT-P, NREMT-P, WEMT, SEAN M. KIVLEHAN, MD, MPH, NREMT-P,SCOTT R. SNYDER, BS, NREMT-P ON MAR 2, 2015

Hyperkalemia treatment is a core skill for emergency physicians and an area in which we excel. Give calcium to stabilize cardiac myocytes if there are ECG changes, insulin (plus dextrose), albuterol, and sodium bicarbonate to shift potassium into the cell, and then sodium polystyrene sulfonate (SPS; brand name Kayexalate) to eliminate the potassium from the body, right?

There are areas to debate within each of these steps, but I want to address the final one. SPS is a cation-exchange resin that was approved in 1958 as a treatment for hyperkalemia by helping to exchange sodium for potassium in the colon and excreting potassium from the body. The wide adoption of SPS for this indication comes from two articles published in the New England Journal of Medicinemore than 50 years ago.

Treatment of the Oliguric Patient with a New Sodium-Exchange Resin and Sorbitol; A Preliminary Report

Flinn RB, Merrill JP, Welzant WR New Engl J Med 1961;264:111Flinn and colleagues studied 10 patients with severe oliguria that were given a cation-exchange resin and sorbitol (n=7) or sorbitol alone (n=3) along with no-potassium diets. They found that potassium decreased by 0.5 mEq on the first day and a total of 1.0 mEq after two days. Sorbitol alone was just as effective. They noted that a dose of around 40 mEq/day should be the recommended dose, but this is based on no data or reference of any kind.

Management of Hyperkalemia with a Cation-Exchange ResinScherr L, Ogden DA, et al. New Engl J Med 1961;264:115

This slightly larger study looked at 32 patients with acute or chronic renal failure who were given oral or rectal SPS along with a low- or no-potassium diet. Scherr and colleagues found a mean decrease in potassium at 24 hours of 1.0 mEq.

The Flinn and Scherr studies conclude that the use of cation-exchange resin plus sorbitol is beneficial to treat hyperkalemia. The results of their studies, however, simply do not support this conclusion. The Flinn study looked primarily at outcomes 120 hours after administration. This is hardly the endpoint that we care about in the emergency department. (I would argue that even the inpatient clinicians wouldn't care about this endpoint.) The Scherr study had no control group, and the decrease was seen at 24 hours. Again, not what we would care about in the ED. Both studies lacked even a modicum of randomization, and all patients were given low- or no-potassium diets. These studies from the New England Journal of Medicine are the basis upon which kayexlate has been prescribed for five decades, and it's pretty clear that they prove nothing.

The scant literature on this topic was summed up in a Cochrane review in 2005 that stated that potassium-absorbing resins have never been found to be effective in the first hours of treatment. (Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005; http://bit.ly/1HWfR4W.)

A review of the literature shows that there is virtually no benefit in the emergent setting for SPS. But is there a downside? Of course, though we are talking about a rare but highly lethal complication of the drug: colonic necrosis.

A number of case reports and case series detail patients with SPS-associated colonic necrosis. (Surgery 1987;101[3]:267; Am J Kidney Dis 1992;20[2]:159; J Trauma 2001;51[2]:395; Am J Emerg Med2009;27[6]:753.e1.) In fact, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration added a warning in 2011 cautioning against the use of the drug for this reason. (http://1.usa.gov/1DHhPLp.)

Given the absence of any significant benefit, particularly in the emergent setting, and the potential for serious harm, this recommendation from the nephrology literature seems very reasonable: “It would be wise to exhaust other alternatives for managing hyperkalemia before turning to these largely unproven and potentially harmful therapies.” (J Am Soc Nephrol 2010;21[5]:733.)

Initially, it's worth briefly discussing the recent publications highlighting two new drugs targeted at eliminating potassium. Sodium zirconium cycloscilicate and patiromer are cation-exchange drugs, and studies on these drugs have been published in high-impact journals. (New Engl J Med 2015;372[3]:222; JAMA 2015;314[2]:151; New Engl J Med 2015;372[3]:211.) Both drugs have been hailed by researchers (all with significant conflicts of interest) as highly successful in managing hyperkalemia. Before we get too excited, though, both agents have only been studied in small groups of patients with mild to moderate asymptomatic hyperkalemia and not in ED patients. The primary outcomes in these studies were potassium reduction over weeks, which is an outcome that's not relevant in ED patients.

So what should we do with the hyperkalemic patient?

* If he has EKG changes, give Ca2+ salts and standard temporizing therapy and get the patient dialyzed if necessary.

* If you have to wait for dialysis, continue to redose your temporizing meds.

* Look for the underlying cause. Missed dialysis? ACEI? NSAIDs?

Save your patient, yourself, and your nurses from dealing with the unpleasant after-effects of SPS (i.e., diarrhea) by avoiding this ineffective and potentially dangerous medication.

Read more at:

http://journals.lww.com/em-news/Fulltext/2015/10000/Myths_in_Emergency_Medicine__Kayexalate_for.3.aspx